In a

comment on my last post, Gene Phillips made a pertinent observation about my

use of ‘comic book logic’, noting (rightly) that “it's

a tradition that long precedes comics. The original TARZAN novel is full of

"comics logic," both in the way the ape-man teaches himself how to

read, and in the way he manages to become a muscular super-stud rather than

looking the way REAL feral human beings look.” And, indeed, most

iterations of comic book logic (CBL) are an ingrained part of the tradition of

popular and pulp fiction, and most certainly do historically precede both comic

books and pulp fiction; I think it wouldn’t

be too far-fetched to find examples of it not only in medieval chivalric

“romances”, but also in Classical Greek literature and mythology. This being

so, I feel it necessary to elaborate a tad bit more on my use of Comic Book Logic.

Mainly,

because I think it differs in a crucial point from the common use as

illustrated by the Tarzan example adduced by Gene – in itself as comic book

logical as one can expect. Lets consider, for instance, the loose definition

William Goldman uses to describe what he deems ‘comic book movies’ in his

fascinating memoir Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood

(1983):

(1) Generally, only bad guys die. And if a good guy does kick, he does it heroically.(2) There tends to be a lack of resonance (…); it’s not meant to last.(3) The movie turns in on itself: its reference points tend to be other movies. (…)(4) And probably most important: the comic-book movie doesn’t have a great deal to do with life as it exists, as we know it to be. Rather, it deals with life as we would prefer it to be. Safer that way. (Quoted from the 1997 reprint from Abacus, London).

On first

reading these points, one feels, undoubtedly right, that Goldman equates the

comic-book movie with what we would call a ‘pop-corn movie’, the kind of film

one parks the brain in the foyer and enjoys in a state of mindless stupor.

Nothing wrong with either of them, nor does Goldman cast aspersions on their

enjoyment. If I have some contention

with any of these four points, it’s with the implied criticism of so-called

“escapist” entertainment, and (again, merely implied) support for stale realism

in point (4). Of these four points, number (3) defines what may or may not be a

characteristic of comic book logic, post-modernism, and, along with point (2),

somewhat debatable, have no great import for what I intend to address.

However,

points (1) and (4), taken by themselves, or in tandem, offer some valuable help

for me to formulate my meaning of CBL. Lets begin – as we should – with point

(1). In my thirty years of reading comic books (from the time I’ve ditched

Disney and started first reading the Belgian and French bandes desssinées published in TINTIN

magazine, and then DC and Marvel) I’ve lived through a good dozen deaths of

super-heroes. And, in the main, super-hero comic books conform with point (1)

of Goldman’s list of rules. Bad guys have a higher mortality rate than good

guys, and good guys do die great epic deaths.

The first

super-hero death I remember reading was Jean Grey’s at the climax of the ‘Dark Phoenix

Saga’ in UNCANNY X-MEN #137 (1980). At

first sight, Jean’s death conforms to each and every pointer to ‘comic-book’

death per Goldman: it is one of the most heroic deaths one can remember and,

deservedly so, it remains at the top of any list of Great Comic Book Moments.

Jean’s death is unquestionably heroic, but is it a ‘comic-book’ death?

Not to my

thinking. Obviously, the sacrificial hero is a central tenet of the Christian

mythology, and surely predates it for several centuries. Christ’s sacrifice on

the cross (in itself a cheat, as in true comic book fashion, it has been

retconned throughout the centuries intro being a self-sacrifice with

pre-assured resurrection) lacks the over-the-top heroic quality of Phoenix’s

death, opting instead for a weighty dramatic core that apparently removes it

from the canon of ‘comic-book’ deaths.

However,

Claremont’s take on self-sacrifice was a winning and rewarding bet. Instead of

going for the ages-old hero-sacrifice to save the Universe from whatever threat

endangering it (or from Evil, as in the Christian cannon), Jean is dying to

save the Universe from herself. That she chooses a moment of battle adds an

epic dimension to her death, but what makes it really memorable – as corny as

it may sound – is that her sacrifice is framed as the apex of a love story. A

love story that Byrne’s artwork elevates to cosmic proportion through the

identification of its flame with the explosions from the fight on the Moon and

the all-consuming light of the Sun. If ever a succession of three panels so

perfectly condensed the theme of one story it surely was the one above these

lines. And, I’m sure you’ll agree, dear reader, these three silent panels are

soaring with epic music, an unheard soundtrack that echoes the music of the

spheres.

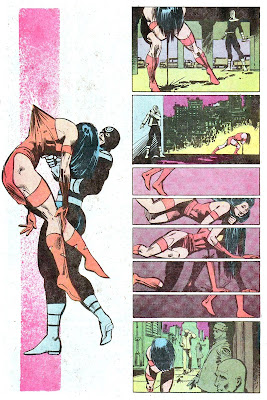

Then came the

bloody, cruel, gratuitous, totally unexpected and devastating death of Elektra

Natchios in DAREDEVIL #181 in April

1982. I do remember seeing the cover of that special issue (then in Portuguese,

but with the same layout if I remember correctly) promising “Bullseye vs Elektra. One wins. One dies.”

and thinking, shit, there goes my favorite

Marvel supervillain! Alas, that was

not to be. Now, maybe I felt Elektra’s

death more than most for I and a good friend had also created a Greek female

character for a project we were writing (both of us in high school), and

Elektra worked as a personality model for her. We were so in love with her. She

was gorgeous, and implacable, and a skilled fighter, and yet so… unexpectedly humane.

And so, to see her stumbling and bleeding as she dragged herself to a cold

painful death in Matt Murdock’s arms… it somehow didn’t seem right. Didn’t seem

fair. And it was a bravado piece of art.

I read

somewhere that the Comics Code wouldn’t allow for the graphic representation of

a blade coming out of a pierced body, that being the main reason Miller had the

blade pushing Elektra’s tunic away from her back. But wow! What an effect. The panel looks like a moment of

imponderability, a nanosecond frozen in time; just that infinitesimal fraction

of an instant before gravity reasserts itself and the blade will come through

the cloth, and the body’s weight will slide the blade impossibly deeper inside

Elektra.

The ninja’s

death is one of the more touching I remember reading. It was in no way an epic

death. It was a lonely death, the outcome of a cowardly trap, a solitary fight

among the garbage and the cold. As if, touched by the warmth of love, having

spared the life of Foggy Nelson a couple of pages before, she had displeased

whatever cold-hearted gods were watching over her. To die at the moment of

redemption is the stuff of powerful myth. And it was the wisest of decisions by

Miller, not to allow her to ever interact again with Matt Murdoch (although it

would have been even better if he had kept his intention of not allowing her to

be used again by Marvel).

And then, also in 1982, came the strongest of

them all: Jim Starlin’s The Death of Capitan Marvel, the

first in the new line of MARVEL GRAPHIC

NOVELS. Fighting a cancer, Captain Marvel died peacefully under the

respectful watch of his colleagues. It is not usual for one to find a moment of

such quiet dignity between the pages of comic books, and it clearly

demonstrates the more mature and adult bend Marvel wished to imprint to its

graphic novels line, pushing it closer in themes and execution to the European bandes dessinées. Never, in my opinion,

did the comics medium, so adroit at getting through the idea of LOUD sounds, so wonderfully convey

silence as in that last panel, with one lonely word calling the readers

attention to what must have been the slowly decreasing intensity of Mar-Vell’s

heartbeat.

The epic dimension of Capitan Marvel’s death is

elegantly displaced into a touching inner fight for acceptance of death itself.

And when such acceptance is reached, Marvel’s alien heart – in a graphic

representation – stops beating in a humanizing sign of the concept of the

super-hero itself, no longer just a super-man, but human, all too human…

These three examples somehow transcend the

comics medium; or, at least, the popular perception of the comics medium as

light entertainment for kids and teens. They certainly contradict Goldman’s

first rule, for here we have three heroes dying in ways that are not epic in

the common sense, although they are undoubtedly moments of undeniable grandeur.

They are not comic book deaths, despite belonging to comic books.

And one other factor made them feel like real

deaths: when each of this characters died, at the peak of their popularity (the

cases of Jean Grey and Elektra), or because they were commercially expendable

(Captain Marvel), their deaths were definitive.

One didn’t come out of the reading with the feeling that these characters would

soon return, retconed or revived, to grace yet more adventurous pages.

And then there came the infamous DEATH OF SUPERMAN. Despite even recent

protestations by writer Dan Jurgens, the greatest comics event of

1993 felt like nothing more than a cheap gimmick. Now, please, let me qualify

this statement: I don’t mean the story, or the art, were poor in quality terms

or as a comics story; hell, even as a comics epic. But, simply, there was no

way in heaven or hell that DC was going to kill not only their flagship

character, but the most recognizable of comic book icons of all time. No way.

The exact moment Superman’s heart stopped beating, there started the clicking

of the clock counting down to resurrection. Every reader knew Superman would be

back. The only question was just when

(just about six months, as it turned out) and how (the silliest way possible).

THE DEATH OF SUPERMAN forever cheapened every super-hero

death that came after it. And boy, once the mortality of superheroes (the diagetic

mortality – not the weird permanence of an eternal present, indifferent to the

flow of time outside the narrative) was removed, they began to fall like flies:

Batman, Captain America, Hal Jordan, Donna Troy, Wolverine, almost every main

super-hero has died at least once over the years. And each and every time, we

knew they would be back. In a more convoluted way, or in a less convoluted way,

after a month or after a year, or after a decade, or in a parallel universe, we

knew that – just like James Bond – they would return.

Besides degrading the face-value of the heroics

currency, THE DEATH OF SUPERMAN

brought about the absolute fulfillment of Goldman’s first rule: now, indeed,

every superhero could die big epic heroic deaths (and more than once, even!),

thus making super-heroes deaths truly comic-book deaths. (On an aside, one can

classify Christ’s death as a comic-book death as well, as we all know he would return as well – I always found

Christ’s sacrifice something like a kind of a cheat, except when watching the

great death scene in William Wyler’s 1959’s BEN HUR.)

On the other hand, THE DEATH OF SUPERMAN underlined an essential characteristic of

super-heroes, highly relevant to the point I want to make about ‘comic book

logic’. Superheroes are not subjected

to the laws of nature. This would seem like a simple lapalissade, but I think one tends to

think of the world of comic books (a lot like the pulp fiction worlds) as not

being wholly subjected to the laws of

nature: men fly, machines fly faster than light, telepaths read minds,

feminists sound clever, a professor and a student become fused as a single

entity and radiation as the most astonishing effects. But I intend to separate

these two propositions as follows: a) in super-hero comic-books, super-heroes

are not subject to the laws of nature; b) everyone else in the same fictional universe

is.

In a way, going back once more into the world

of cinema, I think it’s totally appropriate to comic-books the reading Danny

Peary does of the typical nameless anti-hero of Sergio Leone’s westerns in his Cult

Movies: The Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird, and the Wonderful (1981).

Equating Leone’s anti-heroes with the heroes of mythical Greece, Peary sees in

Leone the working out of the premise of a mythical western era in which “several warriors were blessed with divine

powers to help them in their never-ending combat (…). These warriors were (…)

supermen who lived among mortals”.

And, I think, that’s the only way to understand the working of super-hero comic-books and of comic-book logic; a way that indeed has common roots with pulp literature, but goes somewhat beyond that. And that somewhat will be the point of my next post, when I’ll turn to Goldman’s rule number (4).