When I was a kid, you wouldn’t caught me dead with a romance comic book in my hands. In fact, I never read a Romance comic book in my life, and what led me to DARING LOVE #1 was Blake Bell’s reference to it in Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko (Fantagraphics Books, 2008) as containing Steve Ditko’s first published work (the final story of this one-shot issue, the six-pager “Paper Romance!”). The first thing that stroked my attention was the amazing cover by Bernard Baily, that I appropriately found on a wonderful summer afternoon this past week, not unlike the one depicted on it.

The girl on the cover reminded me of Martha Vickers in 1946’s

THE BIG SLEEP, when Bogart/Marlowe first visits Sternwood’s mansion, legs up to her waist and sunshine in her hair. The golden hay she’s reclining on serves as a rich reminder of the summer heat outside the barn, where one can easily imagine the air shimmering with heat waves rising from the dry ground. A cover about endless summers gone. A wonderfully nostalgic cover, resonant in its clichéd simplicity.

A cover I’m sure I would have loved had I found it when I was a young kid in love with Kara Zor-El. And that led me to think of how would my younger, kidder, self, have found such a comic book like? Yes, me, who thrilled with cowboys and Indians shoot’em ups; who brandished wooden swords side-by-side with the likes of Sandokan and Robin Hood; who played Star Wars with my gunslinger plastic cowboys; who enjoyed binge-reading huge piles of Donald and Scrooge Walt Disney comic books, that were only (albeit, promptly) set aside when I glimpsed my first Superman comic book on the corner’s newsstand where my father used to buy his paper?

Braving beyond the cover, my younger self would have found a world more alien than Krypton, weirder than any of the planets where the Enterprise’s red shirts went to die, peopled by aliens as gorgeous as Supergirl, but as distant as the most sinister creature from the unknown pits of Mongo: women in love!

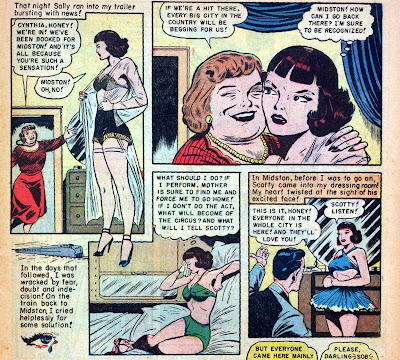

“The Price of Fame”, ALL LOVE #27 (1949), pencils and inks by L.B. Cole

Of course, women in love were a species known to occupy any entertainment habitat, from adventure serials to cerebral science-fiction. They were always hindering, or helping, our heroes. Most of all, they seemed to have the most pronounced proclivity for being in danger and in need of rescue. They were mostly blonde, sometimes brunette, seldom redheaded, and never, never, black-haired. Those were the femmes fatales. The villainesses. But neither of them were ever shown quite like this.

“Dear John”, DARING LOVE #1 (1953), pencils by Gerald Altman and inks by Jon D’Agostino

There, one would have found women in their own secret identities as,well… women, speaking in terms unheard of, as aking to any alien language as Klingon or Swahili, but looking so utterly and unexpectedly gorgeous as any kid could have never imagined on the pages of PALE RIDER or ZORRO.

Of course, I don’t believe I would have recognize them as any of the girls that were usually around my heroes. Sure, they were equally pretty and alluring, but would seldom reveal more than a round shoulder through an expertly torn dress. I wouldn’t ever imagine that even when preparing to brave a snow storm to take some important plea to the governor, our heroine would take care in smoothing her stockings:

“Terror at Tarn House”, LOVE MISTERY #1 (1950), pencils and inks by George Evans

Nor would I ever have imagined, from the height of my twelve-years old innocence, that it could be such a recurrent and sensual gesture, one that we never saw Supergirl or Batgirl performing.

“Too Young to Love!”, INTIMATE CONFESSIONS #2 (1951), pencils by Walter Johnson

And, despite knowing that Supergirl and Batgirl and Wonder Woman had to change from their secret identities to her super-heroine personae, one would never had suspected that under their blouses and skirts any of those wonderful girls – Linda Danvers, Barbara Gordon, Diana Prince – would wear a bra and panties, and least of all, stockings! For all the times one would see Linda Danvers rip her shirt open, just like his more famous cousin, one never got to see what was beneath the blue leotard with the exciting s-shield that always got in the way.

Not so in these Romance comics; here one would glimpse the truth beneath the exterior façade, the secret accoutrements that remained more hidden than Superman’s identity as Clark Kent. When these girls changed clothes, there was always a second tier of intimate protection that bore no resemblance to colorful out-of-this-world costumes.

“Kissless Bride”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #3 (1950), penciller and inker unknown

“The Inner Fire”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #4 (1950), penciller and inker unknown

“Two Wayward Girls”, INTIMATE CONFESSIONS #2 (1951), pencils and inks by Louis Zansky

“Love for Sale”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #3 (1950), pencils and inks unknown

“Heartbreak Road”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #1 (1950), pencils and inks unknown

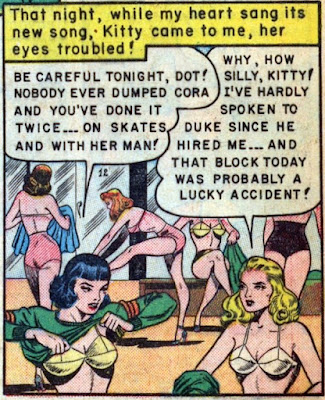

Although their conversations and musings kept sounding like alienese, one would win insight into the they-to-day life of these strange and fabulous creatures. One would follow them into the locker-room and be privy to what went on in there.

“Hate on Skates”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #4 (1950), pencils and inks unknown

And, in the late hours of the night, we would accompany them in the stifling heat, in the inner turmoil of the senses. Unlike the girls we saw in other comics, these women were seemingly incapable of sleep. Their nights a sensual storm of sheer negligès and naked flesh, tousled hair and parted lips, tears and rain and heat. Body heat. Mind fever.

“Dear John”, DARING LOVE #1 (1953), pencils by Gerald Altman and inks by Jon D’Agostino

“Paper Romance!”, DARING LOVE #1 (1953), pencils and inks by Steve Ditko

“Man not for Sale”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #1 (1950), pencils and inks by Reed Crandall

“Girl-in-Waiting”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #3 (1950), pencils by Norman Nodel

“Doomed to Silence”, INTIMATE CONFESSIONS #2 (1951), pencils by Louis Ravielli

“No Substitute for Love”, INTIMATE CONFESSIONS #6 (1952), pencils and inks by unknown

For someone totally unaware of Romance comics (as was I when I read mainly comics) it may come as a surprise the important role they’ve played in the medium. A greater surprise may be to find out that the Romance comics concept was “created” by such giants as Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, responsible themselves for the creation or co-creation of many of the greatest comic book characters of all time. And no lesser a surprise derives from the knowledge that many of my favorite artists dwelled there – and Dick Giordano comes immediately to mind – putting their names to something that goes way beyond the – to me, at least – uninteresting plots: the gorgeous art, in its close-to-reality depiction of mostly dream-like real girls and real women. Romance comics were born still in the Golden Age with Simon and Kirby’s YOUNG ROMANCE (1947-1975), and would cross the entire expanse of the Silver Age, well into the Bronze Age of comics, as an invisible, yet always-present, companion to the more famous and popular super-hero books from the sixties onwards.

In his DC Comics: A Celebration of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes (Virgin Books, 1995, 2004), Les Daniels quotes DC executive Irwin Donenfeld as stating that Romance comics “weren’t sexy in any sense of the word” (p.107). Maybe that’s a perception influenced by Donenfeld’s analysis that Romance comics were read mainly by young girls. Or maybe because they came to an end when the Sixties cultural and social revolution brought about a new, more explicit, sexual mores. However, for the twelve years old kid that never read Romance comics that is a point hard to sustain.

“Hate on Skates”, FORBIDDEN LOVE #4 (1950), pencils and inks unknown

Through mostly inspired good girl art, Romance comics provided an unexpected peek into the lives – real or imagined – of the female of the species. Allowing us to look over their shoulders and into their rooms, under the pretext of caring for their love troubles (that are, along with death, the troubles of us all), these books gave us the chance to admire the female anatomy at its barest, something other comic books – for boys – seldom did. As such, they are, by themselves, an education, a schooling, and a revelation. Something my twelve-year old self would like to have seen then. And so here it is now, in memory of Summers long gone.